It is no secret that District 2 has diverse ecosystems across its territory, ranging from grasslands and lush forests to rocky canyons. Just take a drive down the scenic U.S. Highway 12 or U.S. Highway 95 corridor through Riggins to truly appreciate North Central Idaho’s rugged splendor. However, this surrounding beauty can present unique challenges for the highway, so geologists, engineers and operators must be prepared. A prime example was demonstrated in the November 18 emergency rock scaling project on US-12 near Arrow Bridge.

After a drone reconnaissance of the slope was completed, D2 geologist Garrett Speeter’s assessment leaned toward urgency. With vital information and excellent drone footage in hand, District Engineer Doral Hoff made the executive decision to initiate the methodical removal of the slope. It was all-hands-on-deck and the team promptly got to work.

Now that this November project is well into the books for the district, Speeter would like to highlight notable cost savings and safety benefits provided by UAS platforms (Unmanned Aircraft System). Listed below is a play-by-play analysis generated by Speeter to highlight the drone’s maximum potential on the project.

Figure 1. Front of Skydio X-10 drone including its specialized lenses

D2 recently completed a well-documented emergency scaling project on US-12 at MP 15.5 near Arrow Bridge. UAS (drone) operations played a vital role in the safety scaling, hazard removal, and safety assessment processes of this project. During the project, a District 2 owned and operated Skydio X10 drone (Figure 1) was utilized to monitor the removal of hazardous loose basalt outcroppings above US12.

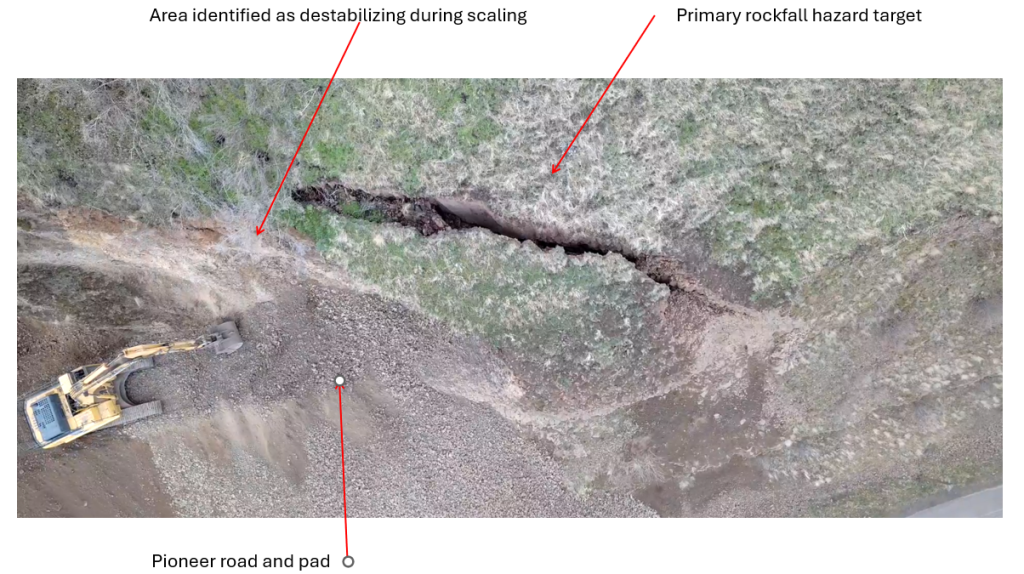

The drone allowed ITD geologist, Garrett Speeter, to monitor the safety scaled slope as unstable material in the hazard outcropping was removed by an excavator parked on the pioneer road and pad located below and adjacent to the hazard (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Excavator as seen from above removing hazard.

While watching both the hazardous outcropping and the safety scaled slope above the excavator, ITD personnel were able to watch for hazardous movement in real time to ensure the safety of the excavator operator. Constant communications, utilizing handheld radios, with both the scaling crew and the excavator operator was a critical safety control. This allowed ITD personnel to use the following abilities during scaling:

- Ability to pause work and then direct safety scalers to remove hazards identified by the geologist. Upon removal of the identified hazard, the team then resumed work in a safer environment (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Loose rock identified as a hazard by geologist awaiting removal by safety scaling crew.

2. Ability to stop the excavator and have it moved if the safety scaled slope began to destabilize (Figure 4).

3. Advise the excavator operator on the status of the crack above the hazard and guide the safety scaling effort in a safe controlled manner.

Figure 4. Excavator parked while crack in highwall is assessed.

Figure 5. Excavator removing the area that began to destabilize above the pad during scaling as directed by geologist piloting the drone.

“The use of District 2’s UAS was a critical tool for the safety and mobility of the traveling public (both on US-12 and the Clearwater River), the rock scaling personnel, the excavation operator and ITD personnel. The ability to accurately and instantaneously assess the stability of this unique hazard was paramount to this project’s success.”

The UAS (drone) platform served as a tool in the safety scaling that allowed ITD personnel to easily and accurately access the temporary stability of the hazard to reopen the road after the work was completed each day. Which provided additional safety and mobility to the travelling public (Figure 6).

The drone was flown continually during active scaling and at the end of each shift to assess the area to determine if it was safe to reopen the road.

Without in-house UAS capability, the drone aspect of the work would have needed to be contracted out. This was unlikely to occur on the project’s timeframe nor would it have been practical given the unpredictable nature of the project. However, costs for hiring a contactor to fly the missions “as-flown” on the project would have been at least $12,000 plus lodging and travel expenses. These costs were saved by conducting the UAS work in-house conducted by personnel already required to be in the field on the project. Therefore adding zero additional labor cost to the project for a true savings of at least $12,000.

Speeter identified a need to be creative with a drone in real-time operations, the cost savings were significant in-house, and most importantly it enhanced safety for everyone on the project. The drone was an excellent resource for not just Speeter in his evaluations but for all crews on site to understand the slope better. As the adage goes “a picture is worth a thousand words.”

Additional notes about slopes and rock fall mitigation from Speeter:

Unstable slopes are challenging to remediate due to variable site conditions throughout the district. Relevant factors in slope stability remediation projects include but are not limited to:

- Lithology and the related associated mechanical properties.

- Orientation of the slope combined with orientation of natural weakness in the material.

- Weathered state of the material.

- Composition of the soils.

- Ground and surface water conditions.

- Support from vegetation (example tree roots).

- Changing temperatures each season/day.

- Scour potential.

There are many proactive ways to remediate an unstable slope including using rock scalers by actively dislodging loose materials with prybars or airbags, jacks, water jets (not as favorable with environmental teams), heavy equipment and explosives if necessary.

Due to the nature of the weathered partial columnar structure of the basalt on site blasting was not a practical option due to the formations inability to maintain an open hole for placing cartridges or explosives. Safety scaling followed by the excavator removal eliminated the hazard in this case. Being able to safely do this work and have the data necessary to reopen the road after safety scaling and excavation was made more safe, efficient, and cost effective through the use of in-house UAS (drone) systems.

This project had unexpected equipment delays (broken starter on excavator) as well which, when combined with an already expedited schedule, would have made hiring a consultant drone pilot even more costly and complicated in an emergency response situation.